Commentary

-

Ann Neumann Questions

Questions for Ann Neumann

How do you keep the AI exhibit from going out of date in a few months?

Many of the state-of-the-art models are currently proprietary and may not be fully understood, so how do you work around that when designing an exhibit?

How long did it take to design the AI exhibit what was the timeline like? How long will it take to react to current changes?

How is the AI section of the museum going to deal with Marvin Minsky and his controversy?

Who made the poem generator? Was it fine-tuned in hours by the MIT Museum made in a lab, etc?

-

The future of AI in museums

I thought that both of these articles are very interesting, but seemed a bit out of date. This use of AI described by both articles has been in use for a long time (some of which I forgot are technically classified as AI). This gives me the sense that museums are quite far behind in using this technology. For the first article, I was interested in the robot art critic. I did not think this was a good use of AI, as first, people do not do a good job of physically showing their sentiment towards objects at museums, and second, I do not know what value this adds for the visitors. I think what is important at a museum is that visitors get to form their own opinions about the objects, and get to decide for themselves what is their favorite. This sentiment analysis can be useful for the museum, but I do not see how this technology in the form of a roaming robot helps enhance the guest experience. For the second article, I also felt that this was a very limited use of AI (and again, this is very old technology). I am shocked it took that long to create a portal for metadata generation. I really like the idea of creating new ways to explore the collection, but I think there are much better ways to implement this and promote exploration rather than explicit search.

I think that Generative AI has the potential to revolutionize the museum experience, both at the museum and online. In the future, AI could be used to create personalized virtual tours, suggesting exhibits and collections based on users’ interests and preferences. Additionally, AI could enhance storytelling and interpretation by generating contextually relevant content, such as visuals or narratives, to accompany the existing exhibits. This could lead to more immersive and engaging visitor experiences. As talked about in the second article, using AI to generate data about the collections can make API access much more complete and useful. I think the question that remains is what to do with works that are created by AI. I am personally of the opinion that these do belong in museums, and that the role of a “creator” is going to shift radically.

-

reading AI

A few thoughts on the readings:

- It’s suprising to me that the first instinct for people would be to develop a humanoid robot to interact with visitors – seems very gimmicky. Would be curious to hear how the Smithsonian experiment ended.

CUsueum: THe vitualization of the industry (such as remote visits) suprised me – I didn’t expect musuems to be able to successfully virtualize, and having seen other virtual items I wonder which visitors prefer this – is this school groups?

Also interesting was the part on cybersec in the Cusuem article – it really seems lkike they’;re fishing at straws. Most of the data breaches that account for their numbers involve medical data or high-priced PII, along with people who are willing to pay and have money to spend.

-

reading-14-tklouie

I found these readings extremely enlightening about the holistic use of AI in museums. In general, I believe that AI and ML can be used as a buzzword in today’s technology sphere and inventions, it comes to indicate this all-knowing purpose of the future and all-doing system. As the Styx article mentions, many people tend to think of AI as these robot helpers that can interact with visitors, a replacement for a human. I personally have also tended to judge AI with a negative bias because of the promises that tend to come with the buzzword. However, these articles bring up useful and advanced examples of applying AI to solve problems within the backend of museums.

However, AI is still a highly tailored system that needs to work on specific datasets and in controlled environments, which museums provide through their collections. Since these collections are comprehensive and internalized, and often also come with embedded related knowledge already, this is the perfect place for AI to thrive. One massive generative AI piece that I have thought about often is the Refik Andol: Unsupervised piece in the Moma. It is a large-scale constantly generating show based on the museums’ collections. It is a fantastic piece to watch in action, and also has an interesting display that explains to visitors how AI is made. I also believe generative AI can be used in the art form to be a strongly spoken criticism to how AI is treated as an objective creation, when it is truly ingrained with many biases. This brings into question whether it is good to have truly unsupervised generation, or if there needs to constantly be human oversight. I agree with the CHM paper that the project needs to be well defined and with careful requirements.

My final thought is that AI, currently a very text and 2-d image centric, especially even 2-d generation is only picking up in a widespread manner now with Dall-e and other image generator prompts. I am excited to see what 3-d AI generation could bring, not just computer models, but how it has and can change fabrication techniques, and consequently human-computer interactions, in the future.

(Reposted ?? I’m having trouble publishing my readings on github they don’t seem to be consistantly going through)

-

On AI and Museums - JL

On the Brock (2022) reading, a quote that stood out to me was: “external users feel more strongly that anything that allows expanded access to the collection has value”. And from the Styx (2021) reading, I think the general sentiment expressed of paralleling AI to the Internet and that to be left behind (i.e. not integrating and using AI) would be like not using digital media or leveraging huge potential. These ideas come together in the conflict and tension that we’ve already been exploring in class: how do you keep up / utilize AI in a way that’s meaningful and impactful (along the lines of expanding access (Brock, 2022)) while not falling behind (Styx, 2021)?

It’s interesting to note that both these articles are from prior years, before ChatGPT and the seeming boom of AI and generative technologies; even the other two articles, one from Jan 2022 and one from March 2023, almost seem out of date; for myself at least, my Twitter feed and so much media that’s around is harping on how new AI tools are being released every single day and don’t fall behind and make sure you’re maximizing your potential.

With this kind of fervor – and always keeping in mind I/we may be in an echo chamber and we may still be very early in the hype cycle – how can you show visitors what you want to show, engage them in the ways that you want, and keep up? The MSU (2023) blog post written in March 2023 was centered around inviting people to use the AI to create generative art and then the art would be shared by being displayed in and around the museum. I wonder if this is creating the conversation piece that’s desired?

Something interesting could be, since it feels like everyone has something they may want to say / do with the AI, leveraging the museum as an innovative space: granting access to the technologies and then opening up room for discussion and conversation, turning the museum into a social setting for collaboration and conversation. Science is always evolving, right now we may be at a nascent period or a rapidly changing period so right now it feels like we’re in a storm, do we wait for it to calm down or do we do what we can in this moment?

-

CMS AI Reading

I think generative AI has a lot of potential to revolutionize the museum experience by enabling new ways to create, curate, and interpret art and artifacts.

For example, generative AI can be used to create virtual exhibitions that simulate the experience of visiting a physical museum. By generating 3D models of artworks and artifacts, generative AI can create interactive virtual spaces that enable visitors to explore the exhibition at their own pace, in a way that feels immersive and engaging, while also enhancing the accessibility of visiting museums. Generative AI can also be used to restore damaged or incomplete artworks by generating missing parts or filling in gaps. This technology can help preserve the integrity of historical works of art while enabling museum visitors to see the art in its original form. Additionally, generative AI can be used as a tool for artistic collaboration, enabling artists to work together on a shared project by generating new ideas and forms. By working with generative AI, artists can push the boundaries of their creative expression and create works of art that would be impossible to achieve through traditional methods. Among all the potential uses of generative AI, the two that struck me the most were the interactive interpretation, and the learning experience, which were both presented in the reading. In the first reading, it talks about how they designed the little robot that is able to detect people’s reactions to the artworks and learn their preferences. This is a very cool way of imitation that allows the visitors to be more aware of their opinions and expressions. Generative AI can be used to create such interactive exhibits that respond to visitors’ movements and actions. For example, generative AI could also be used to create a virtual sculpture that changes shape as visitors walk around it or a virtual painting that responds to the movements of visitors in the room. For the learning experience, I love how “ Elizabeth Merritt points to a possible AI application in which visitors could eventually interact with historical figures at history museums through chatbots that use the figures’ published writings, archives and oral histories. Imagine having a chat with your favorite painter who’s hundreds of years your senior.” It is something that we can not achieve by traditional museum curation. It presents opportunities for generative AI to be used to create educational materials that help visitors learn about art and history. By generating interactive simulations of historical events or people, generative AI can help visitors understand complex concepts in a way that is engaging and immersive.

Overall, generative AI has the potential to transform the museum experience by enabling new forms of creativity, interactivity, and education. However, it is important for museums to carefully consider the ethical and social implications of using generative AI and to ensure that these technologies are used in a responsible and respectful way.

Enter text in Markdown. Use the toolbar above, or click the ? button for formatting help.

-

aouyang-assignment-14

aouyang-assignment-14

The first article enumerates the ways in which AI can be used in museums:

- Robots to record visitors’ emotions and preferences towards artworks

- Interactive robots to answer visitors’ questions and interact with visitors

- Data analytics to predict no-shows in order to release more tickets

- Image recognition matching pictures with artworks of the gallery

- AI for museum operations to measure and forecast visitor behaviors to save operating costs

- Sentiment analysis of visitor comments

Personally I am somewhat skeptical about 1 and 2, as having an object of human-form running around and interacting with / observing you can be an intrusive experience, and that might not work well with museum settings if some visitors prefer a quieter environment to enjoy the art. 3 reminds me airline oversales, but it seems to be a less defined problem in the museum setting. An aircraft has a fixed capacity limited by the number of seats, and if oversales result in exceeding the capacity, the airline would offer incentives for volunteers to give up their seats. However, the capacity of museum spaces is less well-defined, and oversales without adjusting for the capacity (it’s unlikely that museums would offer incentives or enforce a strict capacity) might result in a worse visitor experience. I am the most excited for 5 and 6, which use AI to improve both the visitor experience and the operational / curation practices, without being too visible and intrusive to the museum experience.

The second article describe a specific museum’s experiments with using machine learning. The blog was written 9 months before the release of chatGPT, before the widely available access of OpenAI APIs. I wonder how the results of the experiment will change with the better machine learning models. I find the following statement interesting, “Throughout the project, it became apparent that the commercial machine learning services are primarily geared toward the needs of commercial customers, for uses in marketing, customer management, call centers, etc… We hope that future experiments with using machine learning tools customized through training on our collection can address these stringent quality requirements.” Based on the numbers in the article, a total of $115000 was spent on this project, including compute and development costs. The budget is very small compared to typical commercial ML projects. Given the budget constraint of the museum (and most likely other museums), I wonder to what extent can models be fine-tuned for museums.

-

AI reading

The first reading was interesting in showing all the different ways AI could be used in museums, in particular to data analytics and how that can be used in a fun way (robotics) that can also interact with visitors. The second reading was also interesting in terms of learning about how an AI system was designed and integrated into the CHM.

It feels like adding AI into the museum experience is inevitable, and I can already think of a lot of potential ethical issues in play because of it. I wonder if there are more interactive ways that teach people about how the museums are using their AI, that can also break down the potential stereotypes people come into the museum with from places like movies and TV shows. A way that’s interactive and on the front-end of the experience, similar to what the Smithsonian is doing. I thought the MIT museums had a pretty cool one with the room, but it’s hard to figure out what it responds to- perhaps a more intuitive and informative + cool experience?

-

AI in the Museums

Styx’s article, “How are museums using AI, and is AI the future of museums?” poses some interesting thoughts and examples of how AI can be used in museums meaningfully. One that I found particularly intriguing was the use of Pepper in the Smithsonian museums. Knowing that Pepper is available to help visitors navigate the museum and answer any questions visitors have can be beneficial to the ease of navigating the museum. But I wonder—knowing that most museums have attendants around exhibits and galleries, is Pepper really necessary? What does Pepper offer that museum attendants cannot? The main thing that comes to mind for me, in that case, is that I assume Pepper is more able to process and deliver information in multiple languages, where not all museum attendants may be able to offer that. This could be especially helpful in busy, international museums, such as the Smithsonians.

As I’m reading this article, I’m thinking about the latest developments in AI and wondering how the use of more recent updates will be utilized in museum spaces. I’m sure it exists somewhere, but I’d love to see how/if museums are using AI art generators to spark conversations about ethics and art, or engaging visitors in creative processes using AI art generators, such as Dall-e.

Brock’s article, “A Museum’s Experience with AI,” seems to echo one of the takeaways from Styx’s: AI in museums can increase accessibility for visitors. Brock explains this in the insights when he points to the generating of alt-text for images or translation of museum materials. It seems as though much of the ideas around the use of AI in museums, from both Brock and Styx, point to the use of AI in less user-centered areas, such as museum databases, as well as the use of AI to increase visitor accessibility.

-

AI in the Museum (Anugrah)

The first article talks about AI from three different perspectives: creating moving exhibits (robots) powered by AI, as a tool to add engaging features to museums (like the selfie finder), and in the background to help power data analytics. I really like the second idea personally - it feels like a really engaging application of AI that can be explained very easily at a high level to a general audience while also increasing the depth of your engagement with the museum. It’s also really easily extendable as generative AI becomes more powerful! One idea I was toying with was trying to use generative AI to create an artwork that summarizes all the art that you saw while walking around a modern art exhibit (just to see what it would look like).

The third idea is interesting - and something that my group is working on for our final project, so I suppose I’ll have a more experienced opinion about how AI will affect museums this way by the end of the semester. The first idea is the most gimmicky, but it could be interesting - maybe I’d change my mind if I actually saw the robot zooming around the museum.

The second article was a little confusing to me - I wasn’t completely sure what the project that the CHM had undergone was really aiming to do. My current understanding is that the museum was trying to create a online system to review all the text, video, and image data they had collected about the history of AI over the course of their existence, as well as to use AI tools to create tagged metadata about each piece of the large online “exhibit”. I think the idea is somewhat interesting, but ultimately not that useful - many of the users had a “lukewarm” reception to it as well.

Part of my issue with the idea is that I just don’t know if the way information is presented in this way is actually that helpful to someone trying to learn about AI. If you’re going to sift through a huge online corpus, I imagine you’d be interested in just taking a real course about AI or reading a few wikipedia articles at which point I presume you’d get the same information but much faster and with less of a time/information bottleneck of having to watch several videos in the museum-video format. Also I suspect that most of the interesting pieces of artificial intelligence happened either 80 or 2 years ago. Almost all the information in between is obsolete or just plain uninteresting. This online collection doesn’t inform the general public about the two big leaps in AI, and is also more clunky than just being able to walk through well-organized educational exhibits.

-

AI in Museums

I thought that Styx’s piece was all-encompassing in the ways in which it elucidated the various ways museums have benefited from AI over the past few years. This part is particularly enticing: “For example, by using AI to predict the amount of no-shows who took advance passes to a museum that operates at capacity, that museum can increase actual capacity and release more tickets in advance, eliminating that loss of visitors and bolstering museum visitorship.”

The sentiment analysis, alongside Google’s Arts & Culture app, Art Selfie, has a great participatory value to the museum world. It combined both technologies while still allowing humans to interact with each other, which, to me, I regard as a superior quality.

However, ethical responsibility remains an ongoing issue that requires the scrutiny of AI’s applications in museums or any other domain. Also, how much AI in the museum is too much? Many of the examples mentioned did not take away from the artwork itself. But with the rising integration of AIs in the museum, one should decide when it’s too much for AI to be implemented in the museum space.

In the Brock piece, I very much valued the use of AI in the backstage museum development “OpenCHM”: “Its core strategy is to harness new computing technologies to help us make our collections, exhibits, programs, and other offerings more accessible, especially to a remote, global audience.”

One interesting thing the article touched upon was designing the portal. They have used sophisticated and expensive technology over the past year. I wonder how that can change with ChatGPT. While it is different, what type of design ideas can be generated if I give ChatGPT certain prompts with specific goals? What types of prototypes can ChatGPT produce? I did ask ChatGPT for that, but I think the most important key is perfecting the prompt.

-

AI in Museums Commentary

The interactive AI in museums mentioned in the Styx article are really interesting. It mentioned Recognition, a matching game of recent photojournalism and art and how this was used both inside the museum and virtually. This seems like a really great way for museums to get visitors to engage with pieces that aren’t currently on display and while visitors are at home. I’m wondering how this looked inside of the museum - would the AI suggest similar pieces, and then if pieces were in the museum’s collection, it could show where in the museum it was? There is opportunity here for AI to be used as a way to get visitors to further engage with the museum as opposed to just being a game.

In the computer history article, I found it interesting that the developers wanted to have users be able to choose between human or machine generated metadata, or a mix. Is this for ethical or security or for comparing the results? Why would they go through the trouble of developing this technology just to also do the work themselves?

This article also brought up using the machine learning services to provide textual descriptions of images for visually impaired people. How could this best be used in the physical museum context beyond a purely digital platform for virtual images? There’s a lot of room to explore here, maybe having an app that scans the work and reads out the description, though this seems as though it would only work in the context of art museums.

-

Museums and AI

How are museums using artificial intelligence, and is AI the future of museums?

This article does a good job of exploring the multiple different avenues through which museums are being affected by AI. While many headlines typically focus on the use of AI in exhibits this article also delves into the important topic of how AI is being used to improve museums as a whole on the service and logistics side. One of the examples the article went into along this front was the humanoid robot Pepper used in the Smithsonian, which helps visitors with their questions and even poses for photos. In the future, I could see AI being used to make information much more accessible to visitors, both about museums and exhibits. Even with our current level of technology, it would be possible for museums to train large language models to answer questions about different exhibits and amenities so visitors could essentially always have a personal guide at their fingertips.

A MUSEUM’S EXPERIENCE WITH AI

In this article, the CHM takes the reader through a deep dive into how AI was specifically incorporated into an effort at the CHM to make collections more easily accessible and searchable. The article delves into the incredible amount of development work the CHM team undertook by collaborating with external partners and utilizing Microsoft’s Cognitive Services. In all the team was able to make a successful prototype of a portal containing digital assets and AI-generated metadata. Although the team originally had much grander ideas in mind about creating a sort of graph view to show the connection between search results, they eventually decided to put that aside to limit the scope of their prototype. The results of the evaluation showed that external evaluators were more positive about the utility of the machine-generated metadata than internal evaluators, and they found that automatic transcription of video and audio items using machine-learning tools seemed to be the most useful feature. In all this article does a good job of illustrating all the difficult development and design work that goes into building AI-enabled services, and the great potential that these services can have.

-

AI in Museums

In the article “How are museums using artificial intelligence, and is AI the future of museums,” the author highlights the potential use of AI in museums and notes that we are still in the learning stage when it comes to using and training AI. They mention how AI can not only provide engagement for the visitors but also help with the museum’s own operations, an aspect I have not seen as much. While having AI in the museum space and interacting with the visitors is an interesting way to showcase AI potential and attract visitors, they can be a lot more helpful if used by the staff themselves. A previous reading mentioned that the modern-day curation process can be complex given how much digital data exists everywhere, and AI could become a more efficient way to help curators and exhibit designers pick and find the right piece of information. AI’s ability to sort through data paired with the decision-making of the human staff could vastly improve and rationalize the choices museums have to make regarding their collections.

While AI is a powerful tool in many aspects, we still need to make sure that they are used properly and responsibly. All the ethical questions around data collection and biases aside, training an AI to perform adequately can still be difficult as demonstrated in “A Museum’s Experience With AI.” Because of the commercial focus of today’s AI architecture and possibly the black-box nature of AI systems, the CHM realized the challenges that come with using AI in a museum. They found that the AI didn’t provide much beyond the original context of the information given and do not offer helpful insights. A different architecture may be needed in order for AI to process museum data in a more purposeful manner, a task that could potentially take a lot of time and effort but could ultimately transform the museums and their ways of dealing with information.

One potential use of generative AI I personally would like to see more of is the AI’s ability to create personalized exhibits for visitors. It is always difficult for museums to accommodate the needs and expectations of every visitor who steps in given the different experiences everyone has. Generative AI might be a way to bridge that gap and offer object labels, recommendations, or even entire digital galleries tailored to the visitor’s specifications of what they want to see. A powerful enough AI like ChatGPT might also be deployed as a personal companion to every visitor, offering them an opportunity to chat with the AI about different objects and gain different insights through the AI’s answers. This does require the AI to be specifically created for the museum’s collections and database while also maintaining a high level of correctness and accuracy, but when done right, it could be a powerful tool that allows different visitors to create their own experiences through their conversations with the AI.

-

AI and Museums

Both readings about AI in museums provided new insights into the role that AI can play in the museum realm. The article “How are museums using artificial intelligence, and is AI the future of museums?” mentions several different examples of AI implementations in museums, such as Berenson, a robotic art critic that records people’s reactions to art to develop its own taste. Another example is Pepper, a robot that interacts with visitors through voice and storytelling. These AI implementations encourage more engagement and deeper thinking from visitors. However, I feel that people may want to interact with the AI simply because it is AI. I am curious about the extent to which a visitor’s motive to engage with the AI stems from a genuine place of interest to learn more about an exhibit and the museum content, or to interact with the AI for the sake of AI. Does the root of why the user chooses to engage matter? On one hand, engagement is engagement regardless of whether the visitor is actually interested in the exhibit or just playing around with AI. At the end of the interaction, they will have more knowledge regardless of their motive. But, I feel that a museum may lose the essence of what they are trying to convey/exhibit under flashy AI robots and implementations. As technologies develop, I think it is even more important for museums/institutions to consider whether the tools they are implementing are necessary or not.

Like the article states, AI tools such as websites, chatbots, and analytics tools can definitely improve the visitor experience. It is mentioned that AI can help improve access visitors have to the museum by predicting no-shows and allow museum staff to adjust ticket capacities. One thing that came to my mind when I read this was the reading on storytelling, and how opening a door is not enough to make underrepresented members of communities feel more welcome in attending museums. How can AI systems allow for more accessibility for all members of society in the museum realm? The article “A Museum’s Experience with AI” gives us insight into how museum collections can be made more accessible to non-english speakers and provides a glimpse into what a more equitable museum experience may look like. In terms of generative AI, there are many potential uses in the museum field. Generative AI can be used to facilitate art restoration projects, create more immersive experiences, provoke imagination and sensory experiences, etc. I envision a future where generative AI is used to enhance museum experiences for people of all ages and backgrounds, allow for more collaborative processes between museum professionals and community members (improving communication, facilitating decision-making, understanding data, etc), and more. With the advent of a new technological age, it is of course important to consider the potential biases that may be embedded in the foundation models of AI systems and how these may translate into the museum realm.

-

A MUSEUM'S EXPERIENCE WITH AI

A MUSEUM’S EXPERIENCE WITH AI

The “A Museum’s Experience with AI” article provides valuable insights into the practical application of commercial machine learning tools in a museum setting. It highlights the potential of these tools in expanding access to collections and enhancing user experience, particularly through automatic transcription and translation of audio and video materials. However, it also tells us about certain limitations of the current experiment with machine learning. The author emphasizes the current state of machine-generated metadata may not significantly surpass standard full-text search capabilities.. Also, the article draws attention to the limitations of commercial machine learning services, which are primarily tailored to the needs of businesses rather than cultural institutions. This suggests the need for customization and training of machine learning tools specifically for museum settings to address stringent quality requirements. Additionally, I agree that it’s important to decouple a museum’s database from specific machine learning services, as adopting a flexible architecture would allow museums to adapt better to changing tools and capabilities.

One thing that AI can do for visitors is to make museums more accessible for them. For instance, AI can automatically generate translation into different languages for foreigners, and also for people with disabilities, AI can even automatically generate sign language for the audio. While AI performs this task, it is important that visitors can clearly differentiate between human generated and machine generated metadata. In this way, users have the flexibility to choose between human and machine generated metadata based on their own preferences and needs.

Another important thing about applying AI in museums is that the AI system developed should be very flexible and ready for change. First, different museums might have varied specific needs, and the AI tools for museums should be easily customized to the given museum using that museum’s unique corpus of documents. Besides, AI models are updating at an incredibly fast speed, so the museum’s database should be decoupled from specific AI services. This would help create a flexible system where machine learning generated data can be easily imported, replaced, or updated in the museum’s database.

-

A MUSEUM'S EXPERIENCE WITH AI

The “A Museum’s Experience with AI” article provides valuable insights into the practical application of commercial machine learning tools in a museum setting. It highlights the potential of these tools in expanding access to collections and enhancing user experience, particularly through automatic transcription and translation of audio and video materials.

However, it also tells us about certain limitations of the current experiment with machine learning. The author emphasizes the current state of machine-generated metadata may not significantly surpass standard full-text search capabilities.. Also, the article draws attention to the limitations of commercial machine learning services, which are primarily tailored to the needs of businesses rather than cultural institutions. This suggests the need for customization and training of machine learning tools specifically for museum settings to address stringent quality requirements. Additionally, I agree that it’s important to decouple a museum’s database from specific machine learning services, as adopting a flexible architecture would allow museums to adapt better to changing tools and capabilities.

One thing that AI can do for visitors is to make museums more accessible for them. For instance, AI can automatically generate translation into different languages for foreigners, and also for people with disabilities, AI can even automatically generate sign language for the audio. While AI performs this task, it is important that visitors can clearly differentiate between human generated and machine generated metadata. In this way, users have the flexibility to choose between human and machine generated metadata based on their own preferences and needs.

Another important thing about applying AI in museums is that the AI system developed should be very flexible and ready for change. First, different museums might have varied specific needs, and the AI tools for museums should be easily customized to the given museum using that museum’s unique corpus of documents. Besides, AI models are updating at an incredibly fast speed, so the museum’s database should be decoupled from specific AI services. This would help create a flexible system where machine learning generated data can be easily imported, replaced, or updated in the museum’s database.

-

“How are museums using artificial intelligence, and is AI the future of museums?"

“How are museums using artificial intelligence, and is AI the future of museums?”

In the article “How are museums using artificial intelligence, and is AI the future of museums,” it’s interesting how the author divides the uses of AI into two parts: direct interaction with visitors and behind-the-scene analytics forecasting visitor behavior. This resembles categorization of museum staff: some serve as tour guides for visitors through direct conversation and others do analytics and curating work behind. However, even when bots are performing basically the same task as human guides in museums, such as answering visitors’ questions and telling stories using voice and gestures, their pure presence makes the whole museum experience more engaging and eye-opening for visitors.

There are many innovative ways through which AI can help enhance visitors’ experience. Not only serving as an additional guide inside the museum, AI can help make the visitors’ entire museum visit experience more coherent and memorable. For instance, to leave a deeper impression of artworks in the visitors’ minds, AI can match people’s selfies with artworks and provide visitors with a matching game of artworks and photojournalism, as mentioned in the reading. Similarly, I believe AI can do more such tasks to make viewers feel like they are being part of the artwork exhibited. For instance, there can be a virtual dress up application, virtually putting attire or costumes from ancient periods (of personnel in the painting) onto the visitors themselves.

AI can also help gap the time difference between the artworks and the visitors. Visitors can be given the power to travel back in time and “create” history with AI. For instance, visitors can have simulated conversations with historical figures, which is actually played by the chatbot. Museums can also use AI to create filters that transform visitors’ artworks or photographs into the particular style of an artist, period, or technique. Using AI in this way shortens the distance between the historical works and the contemporary visitors.

-

Transmedia and Storytelling

I think that the idea of transmedia storytelling is very interesting and practical as well as it really focuses on systematically dispersing integral elements of a fiction across multiple delivery channels, which effectively helps the visitors obtain a deeper impression of the entertainment experience. But I can also imagine the approach to be more challenging for museum design as you need to incorporate different media into one single space.

For my design proposal, I think transmedia works very well because it really aligns with what we were considering: expanding the contextualization of one piece of art through different media such as architectural design, music, VR/AR, tactile and physical interaction, and so on. By telling a story across multiple platforms, transmedia storytelling will allow us to engage with their audience in different ways. It will also encourage audience participation and involvement, creating a more immersive and engaging experience. The primary driver behind transmedia storytelling is allowing us to explore the story and characters in greater depth, as we will have more space and opportunities to develop our narrative. This can result in a richer and more complex story that is able to resonate with a wider audience. By creating a cohesive and interconnected narrative across multiple platforms, our group can generate greater interest and awareness for our exhibition, leading to increased attention from the public.

Question 1: Is the traditional museum unwelcoming to large portions of our society?

There has been criticism that traditional museums can be unwelcoming to certain segments of society, particularly those who come from lower socio-economic backgrounds or who belong to marginalized communities. This is because traditional museums have historically been located in affluent areas, and may have collections or exhibitions that reflect the interests and perspectives of the wealthy or privileged. Additionally, traditional museums may not always be accessible to people with disabilities or those who speak languages other than English, which can further exclude certain groups from experiencing and enjoying museum exhibits. I think it has to deal a lot with the existing social construct throughout centuries as people from lower socio-economic backgrounds are also generally less interested in museums compared to the wealthy, making this issue more concerning. Although many museums have been working to address these issues in recent years by offering free or reduced admission, creating more inclusive and diverse exhibits, and providing accessibility accommodations such as sign language interpretation or audio descriptions, I still think that even the diverse exhibitions showcasing the lower social-economic world tend to target the wealthy. Those who suffered from the situation might not be willing to visit nor agree with the exhibition.

Question 4: How can we amplify the voices of the unrecognized? One way to amplify the voices of underrepresented communities is to collaborate with them in the development of exhibitions and programming. This can help to ensure that their perspectives and experiences are accurately represented and presented in the museum. A similar approach can be hiring and promoting staff from diverse backgrounds. It can help to ensure that the museum is more inclusive and sensitive to the needs of underrepresented communities. Additionally, having diverse leadership can help to guide the museum’s priorities and decision-making processes towards greater equity and representation. To make this come true, one feasible plan is to engage in community outreach efforts to build relationships with underrepresented communities and encourage their participation in museum activities. This can involve partnerships with community organizations, targeted marketing campaigns, and outreach events. Question 7: What if your museum is not ready to engage in the storytelling of the future?

I think this is always a tricky question as return is always highly associated with risk. But just like the financial world, we can conduct measurement and analysis to maximize our return with the minimum risk. For example, the museum can conduct an assessment of its current capabilities and resources to determine where it stands in terms of storytelling and digital engagement. This assessment can identify areas for improvement and help the museum to set realistic goals for the future. Or, the museum can seek partnerships and collaborations with other museums, cultural institutions, or technology companies to leverage expertise and resources. This will ensure the influence of the project of storytelling. Lastly, the museum can always start with small, manageable projects to build momentum and gain experience in storytelling and digital engagement. This can help to build confidence and pave the way for larger initiatives in the future.

-

Storytelling and Museums

In the Amy Hollande piece, particularly the third question on how the underserved community can be reached, I really resonated with this notion of creating “a network of museum fragments, located in everyday places like libraries and hospitals, turning common spaces to common good.” It is just at the core of our group project, the pop-up museum. They should be transferable and thus reach a larger audience, and the pop-up museum can be the epitome of that by strategizing to reach the underserved community. The first question centered on the common theme of our first classes, which largely focused on making museums more welcoming. But, as we’ve seen, this isn’t an easy task, and even if done correctly, it won’t guarantee engagement from the target audience, as the author has stated: “However, they all acknowledged that just because we open a door, it doesn’t mean that new and diverse communities will feel welcome.” The second question on how to reach the underserved community did not provide me with enough actionable data. It wasn’t until I reached the third question that I felt the question was posed in a way that allowed the reader to carefully reflect on the ways in which underserved communities can be served and reached.

In the Soraia Ferreira piece, I think Henry Jenkins’s book Convergence of Culture and its definition “integral elements of a fiction get dispersed systematically across multiple delivery channels for the purpose of creating a unified and coordinated entertainment experience.” is similar to our group project. The utilization of a select few works of art and the implementation of microstories along with VR is what creates a unified and coordinated experience where the VR complements the elements of the artwork and immerses the participant.

In the Ellen Lupton piece, I very much entertained the thought of the silence, the break, and the anticipation moments, just like in the rollercoaster experience. I’ve facilitated at a museum, and when I ask a question and don’t get prompt answers, I assure the participants that it’s okay if they don’t feel like sharing, but what’s important about this story is that I was avoiding the silence, which can and should be inherent in the design of museum experiences in many cases. I believe that the engagement in the pop-up museum should allow for moments of silence as well as moments of anticipation as part of the engagement. The experience shouldn’t always be active or indulging; rather, it should provide a space for the participants to enter a deeper state.

-

Storytelling and Museums Lamees

Storytelling and Museums

Reflections on the Future of Museum Storytelling

Question 1: Is the traditional museum unwelcoming to large portions of our society? One quotation from the text that stood out to me was “just because we open a door, it doesn’t mean that new and diverse communities will feel welcome”. This is important to acknowledge because it signifies that more action must be taken to create a welcoming environment and disentangle museums from their traditional or historical contexts, often rooted in class and privilege. While the door may be “open” to all members of society, many may feel unwelcome due to reasons such as being from socioeconomic, academic, or cultural backgrounds that are underrepresented in museum communities. It makes us wonder what ways we can foster museum experiences that are fruitful and enjoyable to all members of society.

Question 3: How can we best reach underserved communities? I was really intrigued by the idea of MICRO Museums. While it is easy to think about how to encourage people to come to the museum, we often overlook ways in which we can bring aspects of a museum to the people. I previously interned for Design Museum Everywhere, a nomadic museum based on Boston that focuses on bringing exhibits, programming, and activities to communities (mainly around Boston). This brings into question whether a museum necessarily has to be tethered to one physical location. What are the benefits of breaking up a museum into smaller, more portable spaces? How does this allow for more engagement and participation from all kinds of people and communities?

Question 5: How can we design community-first exhibits? My takeaway from this question was that the community needs to be included in all stages and aspects of creating an exhibit, from beginning to end. I am curious about the extent to which existing museums collaborate with communities when creating exhibitions. I think this would aid in lessening the sense of hierarchy that exists between curators/directors and visitors. Maybe co-designing exhibits can be a possible solution to Question 1, creating a more welcoming space to all members of society if they feel more represented within museum processes.

Can You Apply Transmedia Storytelling to Museums? There were many aspects of this reading that I think can be applied to our project. One of the main aspects that I think is relevant to my group’s project is the concept of choice. The audience should have a choice regarding the content they want to consume, as well as the level of participation they want to have with that content. This allows us to cater towards different kinds of visitors: those who prefer a more passive experience, as well as those who are seeking a deeper engagement with museum exhibits. Our project focuses on the notion of prompt and response as a means to facilitate interactions and connections between visitors while simultaneously encouraging them to build a deeper understanding of the exhibits. We have started to consider ways in which we can give them choices regarding the level of engagement they would like to have, such as by having different devices include different activities. However, another option is to include multiple prompts on one device, allowing even more freedom for the visitor. Like the reading suggests, our prompt and response devices must also have a sense of coherency and consistency across the platforms to create a sense of ‘brand visibility’.

-

reading 12 tklouie

Question 6: How can a small museum with limited staff and budget implement such grand efforts?

This question drew me in because it also covers the core of accessibility, essentially what are the bare minimum resources you need to make a museum experience connect with the community. Digital media has been crowned in such a manner for all types of innovation- software, digital creation, all these things that don’t require physical resources to make. I believe that this kind of focus on low resource connections doesn’t have to always be digital, however, and people bond much more in a physical space than via social media accounts. One of the museum’s key assets is the space that it provides and the people who work there, and think more about ways to capitalize on that, maybe with lates or community events that don’t need all the flashy themes and showcasing that take up a lot of resources, time, and planning. Why is opening up a discussion that expensive?

Question 3: How can we best reach underserved communities?

The MICRO Museums concept is very exciting and very intriguing because it falls very similarly to our project theme. This is a much more affordable way to bring museums into spaces that otherwise won’t have any, much like our pop up, but scaled significantly down. I would be interested in seeing how we could combine and integrate these ideas to maybe make a pop up museum, more like a community pop up book store/shelf where people can interact with these objects.

Question 5: How can we design community first exhibits?

With my experience in D-lab for global development here at MIT, I believe the answer to this question follows a very core idea: It is collaboration, where you are working with the community and not for the community. It is so often in research and I believe some of the museum world that the curators can speak for the topic, rather than having a community guided and lead project. Supporting, and rather than speaking, for the community is very rewarding

Since we encounter transmedia storytelling in very compelling ways today, it is really exciting to put a name to it! I think this is a core concept in our project because we are hoping to build out something that is across a variety of media and ways of interaction, where different interactions and presentations will tell an aspect of the art piece. Rather than generating loyalty, it can give the viewer or visitor a lesson to learn and grow from.

-

Assignment 12 - Storytelling and Museums

Reflections on the Future of Museum Storytelling

Question 2: How can we build trust with underserved commuities?

I am particularly interested in this question since I find it to be a very important question that all museums, especially the big institutions need to solve. As museums change to be more inclusive and welcoming in the modern times, it is crucial to find a way to reach out to those who haven’t been able to participate in the conversation about museums and let them know that they can participate. The project at Amsterdam Museum shows how difficult this problem can be given how long it took them, but it is a step in the right direction to include opinions and stories from underserved communities when designing exhibits. Both sides learn from the experience, and the communities can see what efforts the museum is willing to put in for their stories.

Question 3: How can we best reach underserved communities?

I really liked the idea behind the MICRO Museums since it attacks the problem from the fundamental issue of the physical space a museum takes place. While traditional museums can seem intimidating to some communities or groups, the MICRO Museums give them a chance to participate even if they are not specifically looking for the experience. Since the fragments are small and each focuses on one topic, it is easy for people to walk up and engage while performing their original tasks at the local spaces.

Question 6: How can a small museum, with a limited staff and budget, implement such grand efforts?

With the outreach potential of the Internet and various social media platforms, smaller museums now have opportunities to spread their influence much wider than what they can do locally. Interesting projects like the one at the Philbrook Museum of Art can increase the museums’ online visibility and allow them to communicate their message better to a wider range of audiences.

Can You Apply Transmedia Storytelling to Museums?

In my experiences, a lot of museums are starting to take advantage of transmedia storytelling methods from audio guides to mobile apps and online activities. I think our project can definitely benefit from some form of transmedia storytelling since the purpose is to bring together the visitors in a different and interesting way as oppose to traditional talking and conversations. One way to achieve that is to create a way for people to interact over different mediums and across time, which transmedia storytelling can help us to solve the problem in interesting and immersive ways.

-

Assignment 12 Reading - Ani

Reflections on the Future of Museum Storytelling

Question 1. Is the traditional museum unwelcoming to large portions of our society?

The article correctly mentions that most museums are traditionally located in wealthier communities, and typically present their collections from a privileged point of view. While there are many great ways to combat this issue such as opening up museums in underserved areas, one solution I think could be implemented more immediately is to ensure that the people who have a voice in the museum (i.e. curators, designers, etc.) come from a diverse set of background to help ensure that the museum as a space can be more welcoming to people outside of wealthy communities.

Question 4: How can we amplify the voices of the unrecognized?

I found this question somewhat polarizing because on the one hand, I agree that many museums could benefit by doing a better job of recognizing the unheard voices in the stories they tell, particularly in places like history museums where there are almost always several different sides to the same story. I think in cases like The Tenement Museum bringing in unheard immigrant voices to a large online audience is great because that is extending the museum’s core mission. But I think in some cases amplifying the voices of the unrecognized can be a bit less relevant, one example that comes to mind could be a science museum. While there are definitely many examples of unrecognized voices in the history of science if a museum’s goal was to simply demonstrate scientific principles in an interesting manner to its audience these voices may not be as relevant to that museum’s mission.

Question 7: What if your Museum is not ready to engage in the storytelling of the future?

This question brings up the good point that most museums aren’t ready to change the way they do business precisely because they are afraid to change a model they have that is already working. As with most businesses, the only thing that can really force wide-sweeping changes across the industry are strong market forces, so if enough museums are able to implement these new forms of engagement and they become popular enough other museums will be forced to follow to retain their audience. Thus it’s ultimately the will of museum-goers and the dollars that they spend which can enact these changes across the industry, but it is important that some museums make this leap in order for consumers to be able to express their desire for this new type of content.

Can You Apply Transmedia Storytelling to Museums?

Telling transmedia stories can be an effective way to engage audiences and create a more immersive storytelling experience. By dispersing elements of fiction across multiple platforms, creators can reach a wider audience, offer a variety of engagement levels, and deepen the story world. However, it’s essential to ensure coherency and consistency among the different platforms, while staying true to the style of each adaptation medium. Overall, telling transmedia stories requires careful planning and execution, but it can lead to significant rewards in terms of audience engagement and loyalty.

Transmedia storytelling relates to our final project in the sense that data we collect in a museum can be used to create a more immersive and personalized museum experience. By dispersing the statistics we capture across multiple platforms, such as interactive exhibits, social media campaigns, or mobile apps, the museum can engage visitors in new and innovative ways. For example, the data collected from the camera tracking system could be used to generate personalized recommendations for visitors, showcasing exhibits and artifacts that align with their interests.

-

Reflections on the Future of Museum Storytelling & Transmedia Storytelling

Reflections on the Future of Museum Storytelling Question 3: How can we best reach underserved communities? This question captures a key step to welcoming underserved communities into museums, and it makes me wonder how museums measure their reach into various communities. I thought the two projects funded by The Pew Center for Arts and Heritage were great examples of how stories of underserved communities can be highlighted, although I wish the author or the speakers had elaborated on who the audience of those projects were or how they were received. I can think of several different aspects of reaching underserved communities, and I wonder how museum professionals interpret this idea. Is there more of a focus on empowering specific communities through partnering with them, inviting people of underserved communities into museums, or educating people who are not in underserved communities on these communities’ stories? Or something else?

Question 5: How can we design community first exhibits? The community first exhibit at the Santa Cruz Museum of Art & History reminded me of Nina Simon’s participatory museum, and I wonder if it’s the same museum. I find it interesting that the goal of the museum is to tackle a community issue, which differentiates it from traditional museums, which may be established to showcase objects or educate the general public that visits. While a community first exhibit may be much harder to plan logistically with people outside of the museum being involved, that tradeoff seems to have a lot of value as I’m sure active participation in planning leaves a much more significant impact on those communities.

Question 6: How can a small museum, with a limited staff and budget, implement such grand efforts? Like the author points out, social media seems to be a great way for smaller museums to test out or implement initiatives. While staff numbers may be limited and renting out space or organizing physical initiatives all involve a larger budget, the space created through social media and an internet presence is much more low cost to operate in. If executed effectively, an online initiative could attract even more visitors, and if an online initiative turns out to be unsuccessful, the cost to the museum is also much lower.

Transmedia Storytelling I think the inFORM lends itself to several different platforms through which its story can be told. The main thread of the story is the machine itself and user interaction with it. Another way of expanding the narrative is to include video or audio representation of the ideas behind the technology from the Tangible Media Group. A big part of transmedia storytelling can be how museum visitors construct or continue the narrative, so in addition to encouraging visitors to interact with the exhibit, pictures or videos of their experiences that they can share online can also be part of transmedia storytelling.

-

On Storytelling | Some Elements for Discussion - RS, JL

For the discussion this Monday (4/3) on these readings of storytelling, here are some thoughts / questions / provocative ideas / hopefully generative insights that may guide us:

On Hollander’s (2019) questions for the future of museum storytelling:

- What are some examples of museums and institutions that have meaningfully and successfully designed, implemented, and assessed inclusion / community-first initiatives? What can we learn from them?

- Highlighting the question of “how to amplify voices of the unrecognized”: Is this the purpose of museums? A recurring theme of the class has been: what is the purpose of the museum? Is designing community-first exhibits the goals for all museums? Some? What contexts might call for different approaches / reasons for approaches?

- Highlighting the question of “is the museum unwelcoming to large portions of our society”: How might museums address the question of trying to be accommodating to all? If this is the goal, what are some ways museums CAN address all; if this is not the goal, please explain the alternative goals / approaches.

On Ferreira’s (2020) ideas on transmedia storytelling in museums:

- How can museums utilize transmedia storytelling in their work (what contexts)? What are some affordances and limitations of doing so?

- How might museums navigate accessibility and representation in their use of transmedia storytelling?

- What examples of transmedia storytelling in/from museums can be found? What can be learned from non-museum uses of transmedia storytelling? How can those learnings translate to guiding implementation in museum settings?

On Lupton’s (2017) writing on design as storytelling:

- In thinking about the chronosystem – the outermost level in Bronfenbrenner’s ecological model theory (micro-, meso-, exo-, macro- system are the first four, in order – an artifact in a museum is impacted in a way related to the time in which a visitor is experiencing it, and the visitor is similarly impacted in a way related to the time in their lives which they’re experiencing it; is there a way then to capture the dynamic and ever-changing story of an artifact and its experiencer?

- How are the museumgoer’s experience and the hero’s journey related? How are artifacts in a museum and the hero’s journey related? What are ways that this could be utilized in creating a more compelling museum experience?

- Reflect on exhibit layouts that you may have seen recently and/or that have had an impact on you. How did the layout contribute to your experience, and in what ways?

-

The Future of Museum Storytelling and Transmedia Storytelling

Reflections on the Future of Museum Storytelling

How can we amplify the voices of the unrecognized?

David Eng at the Tenement Museum has a really unique approach to this problem. The mission of this museum is so linked to the physical space of the museum, but creating such an intentional digital space was able to effectively expand the impact of the museum. It’s interesting that they chose to expand their audience in the Your Story, Our Story project from those interested in stories of New York City immigrants to those of the entire country, and I’m interested in knowing more about the reasoning behind this choice.

How can we design community first exhibits?

I’m curious to learn more about the logistics of designing an exhibit with over 800 collaborators. The exhibit definitely had a positive impact on the museum and community, and I’m wondering how such a large scale project was coordinated and what it means to have been one of 800 collaborators on such a project.

How can a small museum, with a limited staff and budget, implement such grand efforts?

Small museums may be even better suited to telling stories. They are often already more community oriented than larger institutions and storytelling is an accessible and effective way to engage with local communities. I’m wondering if the “Me Time Mondays” project by the Philbrook Museum of Art is run by a museum staff or a member of the local community - maybe the project could be most effective if both worked together.

Transmedia Storytelling

The article emphasizes that museums don’t need to create new stories, but tell existing ones, and tell them in an engaging way. Such engagement is best created through transmedia storytelling in which mini components of the larger story are told through different mediums. In terms of designing an exhibit to present inFORM, multiple means of communication would definitely be effective in telling the larger story of how inFORM was created, how it is used, and its significance. A large portion of the story we are telling about inFORm will be understood through experiencing it - going through the motions of interacting with the machine, interacting with others, and watching the machine itself. However, text and video explanations and interactions will be implemented to augment the experience of learning about inFORM, how it works, and its impact.

-

Transmedia Storytelling

Transmedia Storytelling

Transmedia storytelling can be an incredibly effective way to engage visitors in our final project of designing pop-up museums. One of our ideas of separating a large painting of a giant into small portions and making those individual exhibition rooms needs the support of a coherent storytelling. For example, for the painting by the Japanese artist, the goal is for the viewers to have this ultimate realization that they have been traveling through only small parts of the painting, being exposed to different body parts of the giant. Therefore, it is important that through framed words on the walls, AR soundscape, and recreation of the sceneries, we can let viewers have a notion of the complete storyline and take note of what part they are going through at the moment. It is similar to the concept mentioned by the author about Hollywood’s approach of transmedia storytelling, which is constructing a world for the viewers instead of simply telling them separate stories.

First, since we are trying to create the sceneries in the painting into a small modelled world, it is important to have coherent room narratives. In the example of the Japanese artist’s painting of a giant, each separate exhibition room represents a distinct body part of the giant. By integrating elements like framed words on the walls, AR soundscapes, and recreated sceneries, visitors will be able to piece together the complete story as they progress through each room, and eventually reach the realization that they are seeing the whole body part by part. A coherent storytelling approach can help enhance the visitor experience by using lighting, scents, and tactile elements to recreate the atmosphere depicted in the painting. We need to focus on the coherency of our design, such as using the same architectural structure, color theme, and installation throughout the different small exhibition rooms.

Also, we can use other aids to make the theme of the pop up museum stand out more to the viewers so that when they exit they have a very clear impression of the overall theme and can have more reflections back home. We can create digital platforms emphasizing the theme of the pop up museum. For instance, there can be videos of background stories, and we can even try to create short introduction videos like the one made by Coca Cola.

-

"Reflections on the Future of Museum Storytelling"

“Reflections on the Future of Museum Storytelling”

Question 1: Is the traditional museum unwelcoming to large portions of our society?

I agree with the article’s point that traditional museums may indeed be unwelcoming to some segments of society due to factors such as their locations, privileged perspectives, and sometimes elitist atmospheres. It is crucial for museums to actively work on dismantling these barriers, welcoming a wider range of visitors, and ensuring that their exhibits and programs resonate with diverse audiences. This could involve rethinking the way stories are told by including narratives that are more recent and relevant to people’s daily lives, as well as involving the community in exhibit development, and creating accessible, inclusive environments.

Another factor that may contribute to some traditional museums being unwelcoming is the lack of representation in staff, leadership, and decision-making roles. A more diverse workforce within the museum sector can lead to more inclusive perspectives and help break down barriers for visitors. Additionally, providing training to staff on cultural sensitivity and accessibility can contribute to a more welcoming environment for all visitors.

Question 2: How to better reach underserved communities?

The idea of a MICRO museum, which is portable and can take place in common spaces such as libraries, is similar to the concept of developing pop-up museums. While it may not be feasible to bring large existing museums to locations of underserved communities, it is possible to create small, movable exhibitions featuring select portions from the museums.

Additionally, to mitigate financial barriers faced by underserved communities, museums can offer free or discounted admission, transportation assistance, multilingual resources, and special services for people with disabilities. In this way, museums can become more accessible and convenient for minority groups.

Question 3: How can a small museum, with limited staff and budget, implement such grand efforts?

Small museums with limited staff and budget can still have a significant impact on their communities by focusing on targeted, strategic efforts. They can start by identifying their unique strengths and resources and leverage them to create meaningful experiences for their visitors.

Another approach for small museums, including pop-up museums, is to concentrate on niche topics, local history, or a more refined collection of works, allowing them to become specialized centers of knowledge and expertise in their communities. With a deeper focus on a few selected pieces, small museums can provide visitors with a more immersive experience. By building a reputation as a trusted source of information and unique experiences, small museums can attract visitors and engage with their communities more effectively.

Furthermore, utilizing social media and digital platforms can help small museums reach wider audiences and share their stories without incurring significant costs. By creating engaging online content, hosting virtual exhibits, or offering online educational resources, they can expand their reach and impact even with limited budgets. The use of technologies like AR and VR can also help small museums create additional experiences, such as soundscapes, when they do not have sufficient funds to support large collections of luxurious artifacts.

-

raw histories reading Livia

I thought it was interesting how photography, as a form of art, is a medium that definitely should be considered and analyzed in a more holistic perspective. It’s more easy to form photo albums with similar themes or a collection of what the photographer wanted, and in a sort of “mass production” sort of style. This is different from other art forms- music albums only come out with a few songs each, or paintings / other works typically stand for themselves or may come as a small part of a collection. But photographs can easily be produced on a scale of hundreds and thousands over a small period of time. In consideration of this, there is much to look at and think about as a museum curator- which photos are important? All of them? Some? Why choose specific ones over the entire thing? What was the photographer trying to express in their work, and what specifically do we want to focus on? Curation seems to be much harder as there is a necessity for selection when there is, essentially, more “data”.

-

Raw Histories Reading Comments

This reading brought new perspectives that I don’t think we’ve encountered so far in previous ones. In particular, Edwards’s emphasis on excavating the histories that surround photographs beyond the actual content of the works was very interesting. The point that “Things have cumulative histories that draw on their significances from intersecting elements in their histories” made me consider how photographs are unique compared to paintings or other forms of art that are more difficult to reproduce and take longer time to create. Photography is more easily replicable, like creating copies of the same photo from its negative, and especially nowadays, the word ‘photo’ may take on more of a digital connotation than a physical connotation. This speaks to how quickly a photo can spread and how tangled its intersections with different people’s histories can be. These factors also shape how different the distribution of photography is from a painting, for example, including aspects like ownership and the production, exchange, and consumption of photos.

-

Raw Histories Comments

Edwards describes photographs as “visual incisions through time and space” - exact recreations of a very minute slice of the world made still. At the same time, Edwards points out that images, in contrast to film, contain a “leveling equivalence of information” which prevents images from taking on a single meaning. Edwards believes images represent a single instant of the photographer’s lived experience that both has the capacity to tell a personal story, but also evade a single literal interpretation. After reading the excerpt, I realized that photography is exactly the limiting case of show-don’t-tell storytelling.

Whenever I see a particularly moving picture I get to put myself in the shoes of the photographer, and try to understand how they feel about it. But at the same time, photographs leave room for viewers to interpret the situation as if the viewer was the photographer themself. Sometimes these photos can accumulate meaning and grow into a “grand narrative”, and other times they are just slices taken out of everyday life.

-

Data Visualization

Max Frischknecht Presentation Data visualization

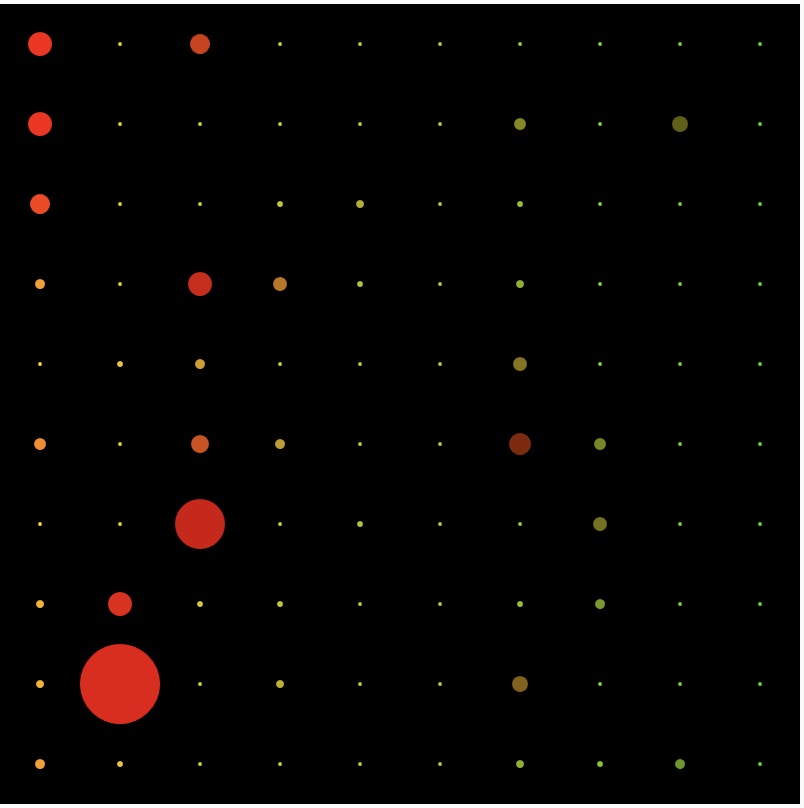

As written in the instructions, I went through the tutorial in the link to Max’s website and working with PIA Metadata API. Results below:

I also took a look at the visualization software, and made some changes to use different data fields to impart some meaning on color as well as location:

I also took a look at the visualization software, and made some changes to use different data fields to impart some meaning on color as well as location:

-

aouyang-assignment11

aouyang-assignment11

Brunner archive’s API

Python Notebook for getting concepts of images and translating them from German to English

https://colab.research.google.com/drive/1jwuIgoGk0M39RIbNjbCHSusaxrWMexTu?usp=sharing

-

Commentary: Elizabeth Edwards - Raw Histories

“Photographs here are as much ‘to think with as they are empirical, evidential inscriptions.” When I read this sentence, I was reminded of how photographs can construct and reconstruct realities, engage in sociopolitical discourse, and serve as evidence to refute or confirm what history books tell. However, I was perplexed by the fact that they are also fluid in the sense that they may contain multiple layers that are open to interpretation and are influenced by one’s ontological dimensions, experiences, cultures, and backgrounds. It’s as the author denotes: “I shall argue instead that within the archive and the museum there is a dense multidimensional fluidity of the discursive practices of photographs as linking objects between past and present, between visible and invisible and active in cross-cultural negotiation.” This then begs the question: How much evidence is sufficient? What level of evidence do photographs hold, and how malleable can that be? Photographs certainly have their powers, but I think they also pose an ethical dilemma, and that the ethical responsibility is contingent on the curator. What history did they choose to reveal, and what history did they try to conceal?

-

raw-histories-tklouie

Raw Histories Elizabeth Edwards Commentary

This reading focuses on the many contextualizations that come from photography beyond the simple subject itself: from the historical/colonial eye, the archival practice of categorizing the photo, future meanings, material, and contextual creation. I found this to be a very comprehensive summary of many of the meanings of photographs I have considered as a photographer myself and as someone who has taken to building photo archives.

A few of the points I found most interesting points include: A difference between public and private photos. Private photos can carry “context with the life they are extracted” and public photos become “removed from such context” and can “generate symbol or metaphor” While I don’t nessicarly agree with the public/private terminology, I believe this is a refined distinction for the purpose of photo taking, and how generally private or personal photos are for one’s own meaning, while once it is shared, the meaning must be contextualized for the viewer to have the same experience. The decision whether to contextualize the photograph or not also leads to different readings.

Photographs will accumulate meaning, and remain Socially and Historically Active objects While the subject of the photo and the image itself is stationary, the effect of photography and the fact that the medium can “constantly pick up new meanings” despite the image being frozen in time. This is the power of photography and reproduction into the current stage. I love the point where an archive of photography is not frozen in time, and can be viewed in many ways in many perspectives.

Photographs construct reality in a performance As they bring historical and non-present snapshots into the current one, the performance of a photo is the current engagement from the viewer and from the presenter. This is beyond the photographer’s realm.

In all, the reading shows the impact of photography and how long lasting these objects can be, despite the singularity of their snapshot in time.

-